Teaching Reflections

-

Failure Leads to Success

Writing failures lead to future successful writing. Most of us don’t like the thought of any type of failure. The word itself has such a negative connotation for many of us regardless of our cultural background. When we set out to complete a project, strive towards a goal, or develop a specific skill set, we often put everything we can muster into the situation. Therefore, when the results come in less than stellar, and we perceive the effort has lead to some type of failure, we find ourselves depressed, saddened, and disappointed. Often times, this process feels like the end of the road, and the individual experiencing the failure must then decide to either try again or walk away.

As a writer, I, too, have experienced this recursive writing process of identifying mistakes made, improving the process, and determining whether I want to pursue the intended goal or dismiss it from the foreseeable future. From an academic perspective, this situation is echoed through returned graded essays. Maybe a student has written what they felt should be an A paper, yet cringed to find a C in bold red at the top of the page. For an author, maybe they thought they had just completed the next bestseller, only to find their book sales meandering next to zero sales. Everyone’s experiences will vary, but one thing remains the same; it happens to everyone.

Collin Brooke and Allison Carr describe this phenomenon best by elaborating, “…in reality, every idea from every discipline is a human idea that comes from a natural thoughtful and (ideally) unending journey in which thinkers deeply understand the current state of knowledge, take a tiny step in a new direction, almost immediately hit a dead end, learn from that misstep, and through iteration, inevitably move forward” (63). Everyone experiences failure in some capacity throughout life. The difference is whether they allow the experience to define them. Finding a way to utilize the lessons of failure in a classroom setting by altering pedagogical structure would be most beneficial to students. “Embracing failure in the writing classroom in these ways makes failure speakable and doable” (Brooke and Carr 63). By changing how we view failure in academic settings, maybe students will begin to see it as just a stepping stone leading to better writing technique in lieu of the end result.

GCFLearnFree.Org is a non-profit organization dedicated to teaching skills that are needed for our modern-day society (2019). In the video provided below, they discuss the recursive cycle of writing and bring up valid points related to learning from failure.

What can we learn from failure? The topic of revision in writing, while often not met with excitement by writers, is a central piece of developing one’s writing, according to Doug Downs (66). As he explains, “First, unrevised writing (especially more extended pieces of writing) will rarely be as well suited to its purpose as it could be with revision. Second, writers who don’t revise are likely to see fewer positive results from their writing than those who build time for feedback and revision into their writing workflows” (66). Downs further explains that revising shouldn’t be an indicator of poor writing. Actually, it should be an indicator of more skilled writing as the author has taken the time to polish and improve the prose.

Contrary to popular belief, I believe it is essential for each of us to remember that as Shirley Rose described, “The ability to write is not an innate trait humans are born processing” (59). Further explained by Moats and Tulman, “human brains are naturally wired to speak; they are not naturally wired to read and write.” Writing, like most things in life, takes practice. The more a writer practices the skill, the more natural the process will become. And, more importantly, failure is the key to success. Each failure a writer experiences will add to the learning. The more we learn, the better we become. So, the next time you feel as though you have failed at something, remember, it only sets you up for future success. Embrace the challenge to try again, and you never know where the trail will lead.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay. 2019, pixabay.com/illustrations/words-letters-disillusionment-416435/

Brooke, Collin and Allison Carr. “Failure Can Be an Important Part of Writing Development.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 62-64.

Downs, Doug. “Revision is Central to Developing Writing.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 66-67.

GCFLearnFree.org. Goodwill Community Foundation, Incorporated, 2019, edu.gcfglobal.org/en/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

“Learning From Failure.” YouTube, uploaded by GCFLearnFree.org, 10 July 2019 May 2019, youtu.be/MQx39z99_Js.

Moats, Louisa and Carol Tolman. “Speaking is Natural; Reading and Writing Are Not.” Reading Rockets, www.readingrockets.org/article/speaking-natural-reading-and-writing-are-not. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Rose, Shirley. “All Writers Have More to Learn.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 59-61.

“The Recursive Writing Process.” YouTube, uploaded by Mometrix Academy, 16 May 2019, youtu.be/WVrvfSFrCwc.

-

Writing: Know Yourself

Who am I? What do I think? How do I feel? What are my biases? Writing, like life, is a series of events and experiences that lead the writer to traverse different paths. Often times, this exploratory process remains in the shadows, out of sight, and unbeknownst to each writer. As participants in our communities and disciplines, many times, we don’t recognize how our perspectives change over time as a result of our life experiences. In other words, we write what we know. However, sometimes, when we write, we don’t realize what we know. An excellent way to learn more about oneself, quite frankly, is to journal. By writing daily about your thoughts, feelings, experiences, and fears, you will begin to notice trends and realize how much you didn’t know about yourself. For more information on how to get started journaling, The Writing Cooperative has a great article that will help you begin an adventure to self awareness.

There are inherent biases in our voices, and those biases contribute to each writer’s message. Tony Scott so adeptly put this concept into perspective, “Writers are not separate from their writing, and they don’t just quickly and seamlessly adapt to new situations. Rather, writers are socialized, changed, through their writing in new environments, and these changes can have deep implications” (49). This concept reminds me of how varied each person’s childhood may be. From the conditions of each individual household, to what types of opportunities and events in which the child is exposed, to the dynamics of the community in which they were raised, no two people will share the exact same experience growing up. This, in itself, creates diversity amongst the masses. We all bring to the table different observations and understandings. Therefore, our writing not only shapes our identities and ideologies, but our identities and ideologies shape our writing.

By the process of being immersed into specific learning disciplines, otherwise known as discourse communities, or being exposed to conventions associated with these disciplines, writers naturally begin to think and associate their own beliefs within a similar theoretical framework as the discipline. For example, an undergraduate Psychology student is learning industry-specific vocabulary, methods of research, and styles of writing related to their specific field of study. After reading journal article after journal article and beginning to understand the process of research, unknowingly, the student will begin to write in a similar style to what they have been reading. The caveat is the student may be completely unaware of their change in writing style. This phenomenon is being studied to further our understanding of how discourse communities contribute to the student or individual developing institutional norms.

Ethnographic (scientific descriptions in regards to customs, norms, and differences among populations or groups of people) perspective is one type of consideration that research is pointing to as a means of identifying specific assumptions each discipline expects students to know before being exposed to the program. Freed and Broadhead’s article, College Composition and Communication, discusses and defines this concept further (163). The information gleaned from ethnographic research would be very helpful for trying to establish a platform for teaching creative writing within a specific community. Below is a short video which explains the value and processes of ethnographic research.

As with all technological advances, the composition of writing has changed over time. As Kathleen Blake Yancey points out, “Writers’ identities are, in part, a function of the time when they live: their histories, identities, and processes are situated in a given historical context” (52). The construct of teaching writing has also changed over time. As Yancey indicates, “Teachers have shifted from teaching writing through analysis of others’ texts to teaching writing through engaging students in composing itself.” Writing used to only encompass the written word, but through advances in the field of technology, writers can utilize images, videos, and sounds to convey a multimodal experience to the reader (53). The diversity of individual life experiences culminating into each writer’s individualistic style creates a paradoxical effect for teachers trying to educate others within the discipline. No two students share the same life experiences, which then begs the question, “Should the instruction of writing be uniform or tailored to the individual?”

Furthermore, as suggested by Andrea Lunsford, “Even when writing is private or meant for the writer alone, it is shaped by the writer’s earlier interactions with writing and with other people and with all the writer has read and learned” (54). A recent University of Florida study determined that what college students read directly affected their syntactic sophistication; those that primarily read journal articles and literary fiction, or general nonfiction displayed higher levels of sophistication (Douglas and Miller, 77). This adds to the level of complexity in how to teach a streamlined process (of writing) across a diversity of students. When it comes to writing, students will always draw upon previous knowledge of how to draft the text, organize the argument, or details of the subject in general (Lunsford, 55).

Works Cited

Douglas, Yellowlees, and Samantha Miller. “Syntactic Complexity of Reading Content Directly Impacts Complexity of Mature Students’ Writing.” www.sciedupress.com/journal/index.php/ijba/article/view/9481/5736

Freed, Richard C., and Glenn J Broadhead. “Discourse Communities, Sacred Texts, and Institutional Norms.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 38, no. 2, 1987, pp. 163. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/357716.

Lunsford, Andrea A. “Writing is Informed by Prior Experience.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 54-55.

Scott, Tony. “Writing Enacts and Creates Identities and Ideologies.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 49.

The Sweet Spot. “What is Ethnography and How Does it Work?” YouTube, uploaded 6 Dec. 2017, youtu.be/_c1SUHTG6B8.

Turner, Eric. “The Best Way to Learn From Yourself.” The Writing Cooperative, 22 July 2018, writingcooperative.com/the-best-way-to-learn-from-yourself-cc9713badd26. Accessed 13 Sept. 2019.

Vesalainen, Tero. Pixabay. 2019, pixabay.com/photos/thought-idea-innovation-imagination-2123970/

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Writers’ Histories, Processes, and Identities Vary.” Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 52-53.

-

The Essence of Writing

Writing Speaks The concept that writing is speaking to situations through recognizable forms is most definitely a multi-faceted concept. As a society, we can only learn and understand information within the limits of language through human communication. Think about that for just a second. Our minds have the ability to dream so much, to analyze, and to understand multi-dimensional structures. We also have the capability of feeling emotions such as love and sadness, as well as other sensory notions that are innately human. But, to express what we are thinking or feeling with someone else requires language; a means of sharing and expressing knowledge with others.

Charles Bazerman, an American university educator, has explained this connection between writing and communication, “Through long practical experience we learn to recognize spontaneously what appears to be going on around us and how it affects us … conscious thought is warranted only if we have reason to believe things are not as they appear to be, if confusions arise within the situation, or if we want to suppress our first impulse and pursue a less obvious strategic path — laughing to appear congenial though we find the joke offensive” (35). In other words, communication is so ingrained in human nature that often times we don’t need to think or analyze our actions in response to verbal cues. However, as our instincts detect a disconnection between what our brain is thinking as our ears are hearing, we then begin to consciously decide our verbal response.

Going further, Bazerman states, “With writing, the need for understanding the rhetorical situation is even greater than in speaking because there are fewer material clues with which to locate ourselves spontaneously” (36). One way the reader can garner these clues that Bazerman references are through the use of genres. Explaining his stance on genres, Bazerman stipulates, “It is through genre that we recognize the kinds of messages a document may contain, the kind of situation it is part of and it might migrate to, the kinds of roles and relations of writers and readers, and the kinds of actions realized in the document.” In layman’s terms, genres could be considered stereotypes to some degree. Through years of communication and experience, readers begin to expect certain formats and criteria found within different types of genre literature. For example, one would expect to find historical facts within the pages of an academic college history textbook and therefore, would be able to process the information within this context. For more information regarding genres, read here.

Another American university educator, Bill Hart-Davidson, further clarifies the concept of genres stating, “ … Genres are habitual responses to recurring socially bounded situations … genre is not something an individual writer does, but rather is the result of a series of socially mediated actions that accumulate over time, genres are only relatively stable” (40). As writers compose literary works, they often adhere to these recognized social constructs as a means of communicating with readers. Over time, slight changes are inevitable, but throughout literary history, many of the classic frameworks still have a prominent place in academic discourse communities.

Mometrix Academy has produced an informative video describing the various literary genres of today; pay special attention to how many of these written works were originally meant to be sung or performed, not just read.

Personally, I find this video to be extremely instructional in regards to the specific types of literary genres found in our culture, and upon viewing, I was able to understand Andrea A. Lunsford’s perspective that, “ … writing is performative … ” (43).

Building upon the concept that writing is a performative act, Lunsford suggests that the performance of writing can go so far as to elicit “spontaneous donations” (44). As I think about the heart-felt stories that have been shared and read on social media sites in forms of Go Fund Me accounts or Caringbridge updates, I begin to truly comprehend the performance dynamics that writing may invoke. I, myself, have made instantaneous monetary donations based upon emotional reactions to various types of written prose. Therefore, I must conclude and as Bazerman mentions, writing most definitely represents the world, events, ideas, and feelings (37), lending to my conclusion that writing is a complex and layered tool of communication.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay. 2019, pixabay.com/illustrations/face-faces-dialogue-talk-psyche-3189811/

Bazerman, Charles. “Writing Speaks to Situations Through Recognizable Forms.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 35-37.

Caring Bridge. CaringBridge, 2019, www.caringbridge.org/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

Charles Bazerman: The Gevirtz School of Education. The Regents of the University of California, 2014, bazerman.education.ucsb.edu/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

GoFundMe. GoFundMe, 2010-2019, www.gofundme.com/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

Hart-Davidson, Bill. “Genres are Enacted by Writers and Readers.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 40.

Literary Devices: Definition and Examples of Literary Terms. Literary Devices, 2019, literarydevices.net/genre/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

Lunsford, Andrea A. “Writing is Performative.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 43-44.

Mometrix Academy. “Types of Literary Genre.” YouTube, uploaded 21 May 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxbDGyLZttA.

William Hart-Davidson: Associate Professor, Associate Dean of Graduate Education (College of Arts and Letters). Michigan State University, wrac.msu.edu/people/faculty/william-hart-davidson/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

-

Ethical Choices in Writing

Writers have the responsibility of making sound ethical choices. As a writer, one controls the words that appear on the paper or the computer screen in front of the reader. Creative writing may be viewed as an art form and expression of self, or it may also be considered a vessel of communication between the author/writer and the reader, with an intended message. Many times writers believe their written words correctly convey their intentions. However, as Bazerman cautions, “ Awareness that meaning is not transparently available in written words may have the paradoxical effect of increasing our commitment to words as we mature as users of written language. As writers we may work on the words with greater care and awareness of the needs of readers so as to share our expressions of meaning as best as we can with the limited resources of written language” (23). John Duffy brings up a good point describing the connection as, “… an activity that involves ethical choices that arise from the relationship of writer and reader” (31). Not only does the writer have influence via persuasive content, but ultimately, their words can have an impact on readers and their lives.

There are several ethical questions that a writer must consider before sharing written works. Some examples of these types of questions are, “What are my obligations to my readers? What effects will my words have upon others, upon my community? (Duffy 31). What obligations follow from my words? What are the consequences?” (Duffy 32). These types of questions are similar to those a moral philosopher would ask concerning whether something is ethical, such as “How should I treat others?” (Shafer-Landau).

Ultimately, when a writer composes a script, whether it be a local reporter typing a piece for the morning newspaper, or a well-known food critic writing an opinion based article about the newest restaurant in town, their words will be read, deciphered, and can have a lasting effect on the community and livelihood of individuals. Could you imagine how detrimental a negative and unprofessional food critique would be for the new restaurant in a small town?

To circumvent some of the ethical issues that would naturally occur in these types of journalism, the Association of Food Journalists’ mission statement and code of ethics guide states, “Our primary responsibility is to share news, ideas, and opinions as fairly, accurately, completely, independently, and honestly as possible.” While guidelines are provided, the Association of Food Journalists’ website specifically states three general questions that should always be considered before a written critique is published: “Am I being fair and rigorous in my reporting process? Am I being honest to my sources, editors and readers about the circumstances surrounding the production and publication of this piece? Am I putting the public’s needs first, or am I making this decision with an eye toward personal or professional gain?”

Aidan White, the director of Ethical Journalism Network, states in this interview (also shown below), there are over four hundred codes of conduct from around the world covering various aspects of journalism. However, he identifies the top five key factors in ethical journalism as: accuracy, independence, impartiality, humanity, and accountability (Ethical Journalism Network, 2015).

Unfortunately, not all writers will follow generally accepted ethical codes of conduct. Duffy describes this concept: “Conversely, an informational or persuasive text that is unclear, inaccurate, or deliberately deceptive suggests a different attitude toward readers: one that is at best careless, at worst contemptuous” (32).

Writers that don’t connect with a humanitarian consciousness write however they want, without regard to any ethical implications to their readers. As a writer myself, I consider it an author’s obligation to contemplate the social impact of my words and to carefully examine my audience for each written piece. The editors of the classroom edition Naming What We Know, summarize the paradigm perfectly when they suggest, “… to be considered successful, all writers must learn to study expectations for writing within specific contexts and participate in those to some degree” (Adler-Kassner and Wardle, 16). However, as Aidan White explains in a 2015 interview (shown below), there is a significant difference between free expression and journalism.

References:

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay. 2019, pixabay.com/photos/hands-earth-next-generation-4086847/

“Association of Food Journalists Code of Ethics.” Association of Food Journalists. www.afjonline.com/ethics. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019.

Bazerman, Charles. “Writing Expresses and Shares Meaning to be Reconstructed by the Reader.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 23.

Duffy, John. “Writing Involves Making Ethical Choices.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 31-32.

Shafer-Landau, Russ, ed. 2007. Ethical Theory: An Anthology. Malden: Blackwell.

White, Aidan. “The 5 Core Values of Journalism.” YouTube, uploaded 19 February 2015, www.youtu.be/uNidQHk5SZs.

White, Aidan. “The Difference Between Free Expression and Journalism.” YouTube, uploaded 18 February 2015, youtu.be/499FWnBDveU.

-

Perseverance in Writing

My writing philosophy closely aligns with Oscar Wilde’s famous quote, “Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.” Although I completely understand there are underlying mechanics of formal writing that many authors follow, and book publisher editorial staffs expect, I also believe that writing is a form of creative expression that shouldn’t be tamed. What I do know about writing, is it means something very different to each author.

Writing styles vary drastically among peers, and for this reason, true art may flourish without boundaries. If everyone used the same syntax, visual structure, or perspective, how bland the world would truly be. Some writers are very organized and methodical; they create outlines, reverse outlines, and design their story, whether formally written or organized only in their thoughts. Other writers use a more free form and write as they go.

Defining “good” writing is quite difficult as it is a subjective analysis based on the preferences of each individual reader. Therefore, I feel as though “good” writing captures the author’s intention. Compositions changed to fulfill a specific genre’s expectations or novels edited to an extreme extent where the storyline is completely changed may increase book sales; but are these changes examples of “better writing?”

J.K. Rowling’s fantasy series, Harry Potter, is an excellent example of this paradox. The book series has sold over four hundred million copies. Upon completion of the first book, Ms. Rowling queried agents and was declined “loads” of times before the London publishing house, Bloomsbury, accepted the manuscript (Gillett). I often wonder what agents who declined the manuscript for not being marketable must think now. Rowling has been identified as the first author to become a billionaire from writing (Carmichael).

A commonly held belief is that writing is easy for successfully published authors. I don’t believe this to be true. At the beginning of each and every manuscript created is a blank page, a pen or pencil, and/or a keyboard. Ms. Rowling speaks to the tenacity and perseverance that all writers must possess and how failure itself will help a writer discover themselves. I believe there is something for all aspiring writers to learn from the most successful female author in history, and it has nothing to do with a financial payoff.

As shown in the following video, Rules for Success, The Top Ten Rules for Success, according to J.K. Rowling, are: failure helps you discover yourself; take action on your ideas; you will be criticized; the process is subjective; remember where you started; believe; there is always trepidation; life is not a checklist of achievements; persevere; dreams can happen; we have the power to imagine better (Carmichael).

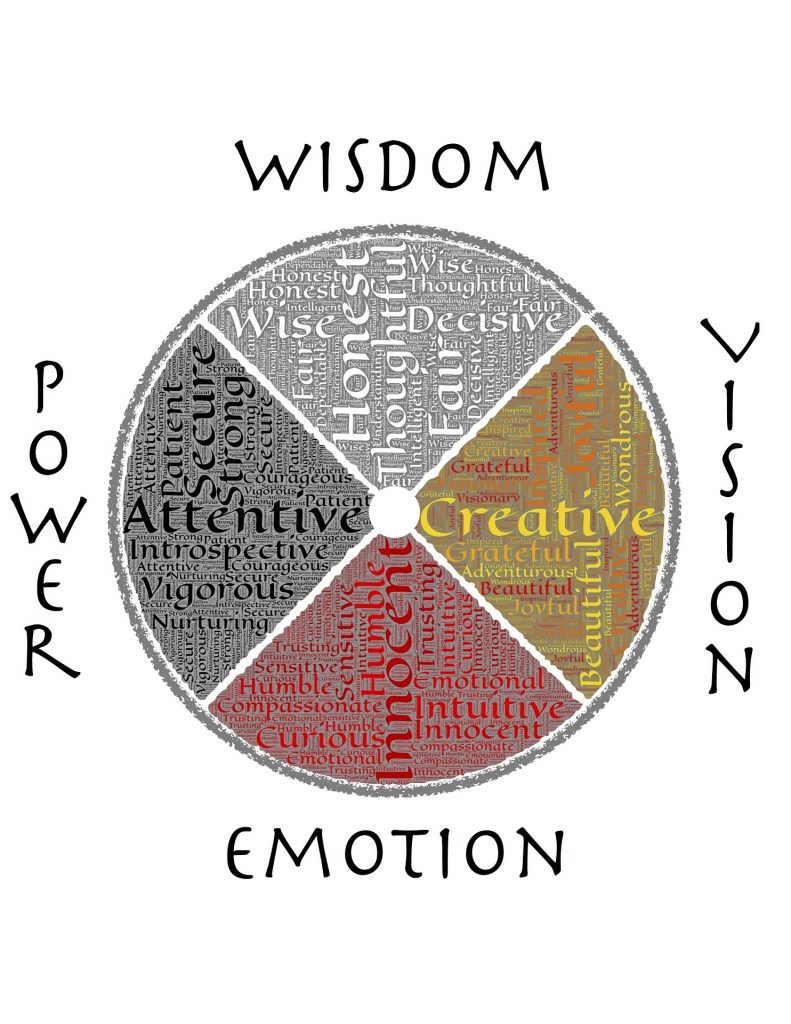

In my future classroom, I hope to utilize a teaching philosophy known as holistic education. Put simply, the foundational approach to this style of instruction is concerned with the student’s ‘whole self.’ It attempts to recognize and understand that each student has various potentials in areas of intellect, emotion, artistic, and creative modes, among others (Wikipedia). Below is a short video that attempts to explain how the holistic educational approach can somewhat fill in the gaps for student learning: What Does ‘Holistic Learning’ Mean for Students?

As a writer myself, I understand the fear of failure and being critiqued on something as personal as bearing your soul on paper. However, following the example of J.K. Rowling, I further hope to help my students embrace the concept of believing in themselves.

BibliU. “What Does ‘Holistic Learning’ Mean for Students?” Online video clip. Youtube. YouTube, 1 August 2019. Web. 25 August 2019, youtu.be/2aFIfCwSEnc.

Carmichael, Evan. “J K. Rowling’s Top 10 Rules for Success (@jk_rowling).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 15 September 2015. Web. 25 August 2019, youtu.be/bvMtUuedLwU.

Gillett, Rachel. “From welfare to one of the world’s wealthiest women — the incredible rags-to-riches story of J.K. Rowling.” Business Insider, www.businessinsider.com/the-rags-to-riches-story-of-jk-rowling-2015-5. Accessed 25 August 2019.

Hain, John. “Medicine Wheel.” Pixabay, 16 September 2014. pixabay.com/illustrations/medicine-wheel-wisdom-power-vision-444550/. Accessed 25 August 2019. Copyright-free.

“Holistic Education.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia.org, 14 August 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holistic_education. Accessed 25 August 2019.