Teaching Reflections

-

FYC Classrooms in the Digital Age

Writing across multiple modes . . . Multimodality — it is a buzz word that tends to bring forth mixed emotions for both professors and students alike. Technology seems to be here to stay, and with the emergence of digital media platforms (social media, eBooks, blogs, and digital learning structures), it has become increasingly more imperative for English composition instructors to expose students to the conventions of writing in these types of mediums. As an incoming English composition teacher, I consider it my duty to prepare students for writing across the curriculum, as well as for life beyond the walls of an academic institution. In previous blog posts, I have thoroughly discussed my intention of structuring the course as a methods-process based design in lieu of product-based only. However, as Alexander Reid explains, “Some writing instructors view emerging technologies with great enthusiasm; others view them as a threat” (185).

Being from a pre-technological advancement era, I understand the apprehension in embracing multimedia components in a college-level classroom focused on writing. With only sixteen weeks per semester and classes that last only fifty minutes three times a week, there is so much to be covered. The question becomes, how do I effectively teach students grammar instruction, writing instruction, composition theory (so they understand the why behind what they are being asked to do), as well as how to write for multiple audiences not only within varying genres but also across numerous modes of publications/platforms?

How to introduce writing across multiple mediums? The question is actually quite daunting, and while I find myself in this very scenario, I try to remain focused on Reid’s perspective, “Writers write. A course that takes as its objective the development of writers must begin and end with writing as an activity, and the amount of writing that students do should not be limited by the instructor’s ability to respond to the writing” (187). Bingo! My takeaway is this — just keep students writing! Regardless of the platform used, genre, or audience targeted, all writing and assignments do not need to be instructor graded. Since writers write, what better way to continuously support the course objectives and learning outcomes than to consistently provide students the opportunity to . . . JUST WRITE!

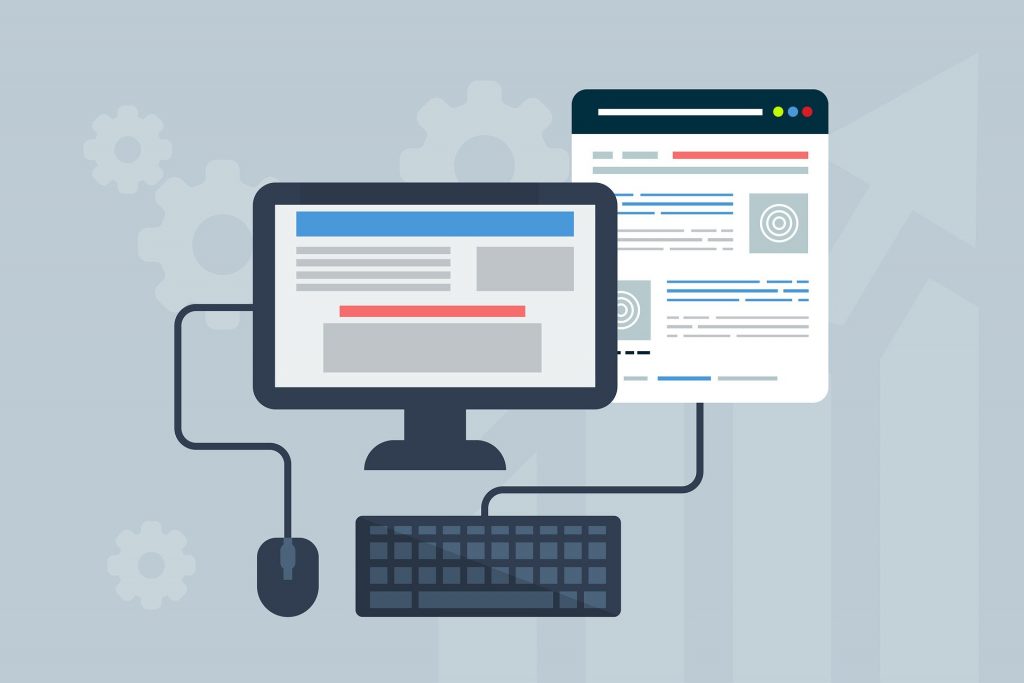

Just Write! Keeping the concept of “writing” in mind, while attempting to continuously expose students to multimodal writing, I have begun to design unit four of my English 1101 course design. The final project/essay will incorporate light research and multimodality. Students will research a topic (still working on the exact nature and/or origin of the topic) and compose an annotated bibliography to organize their research and prepare for English 1102 (the second course of the one-year sequence). Students will be expected to write a summary/analysis of research that will be relatively short, approximately 2-3 pages plus works cited page.

Next, students will utilize the same research information from the essay and create a multimodal project.

Examples of multimodal mediums that may be incorporated into the final product are blog posts, brochures, webpages, and PowerPoint presentations.

Multimodal Writing . . . The purpose of the assignment is to teach students first-hand how writing can be adapted not only across various genres but also across varying mediums. Technology is here to stay, and finding a way to incorporate said technology in composition classrooms will only strengthen students’ confidence in the art of writing, as well as provide real-world examples of why the concepts taught in English composition are of vital importance to life outside of academia.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/light-bulb-think-idea-solution-2010022/.

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/interaction-social-media-abstract-1233873/.

Pexels. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/photos/adult-diary-journal-notebook-book-1850177/.

Reid, Alexander. “The Activity of Writing: Affinity and Affect in Composition.” First-Year Composition: From Theory to Practice, edited by Coxwell-Teague, Deborah and Ronald F. Lunsford, Parlor Press, 2014, pp. 184-210.

Tumisu. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/blog-blogging-blogger-computer-492184/.

-

Rhetorical Grammar: The FYC Classroom

The art of written rhetoric . . . In Making a Case for Rhetorical Grammar, Laura R. Micciche introduces a very persuasive argument in support of teaching rhetorical grammar in composition classrooms. Micciche surmises, “The study of rhetorical grammar can demonstrate to students that language does purposeful, consequential work in the world — work that can be learned and applied” (716). Furthermore, Micciche elaborates, “We need a discourse about grammar that does not retreat from the realities we face in the classroom — a discourse that takes seriously the connection between writing and thinking, the interwoven relationship between what we say and how we say it” (718).

I must admit, I agree wholeheartedly with Micciche. By teaching students to edit and ‘polish’ their grammar in the final drafts of essays and written assignments, we are teaching them that grammar does not have a function in eliciting desired reactions (utilizing rhetorical appeals in persuasive arguments). Instead, we are teaching students that grammatical editing simply changes sentence structure and punctuation to conform to the prescriptive style of writing. As a tutor in the Kennesaw State University’s writing center, I can say from personal experience, this often translates to students being primarily concerned with comma usage and how to avoid the infamous comma splice. However, there is so much more to be discovered in the underlying premise of understanding and utilizing grammatical choices in writing.

Rhetorical choices in composition . . . Micciche references the book, Rhetorical Grammar, authored by Martha Kolln and Loretta Gray, as a resource. Last semester, one of the courses I took in the professional writing graduate program required Rhetorical Grammar as one of the textbooks. This book changed my life as a writer — literally. For some reason, I had to make it all the way to graduate school to identify a resource that not only provided a concise work about all things grammar-related, but it explains rhetorical choices through the usage of grammar as a way of achieving a writer’s desired results. Micciche further argues, “I am talking about rhetorical grammar as an integral component of critical writing, writing that at minimum seeks to produce new knowledge and critique stale thinking” (721).

Designing an English composition classroom . . . Each professor must individually decide the role rhetorical grammar will play in their classroom. For me, concepts found in both Rhetorical Grammar, and a book written by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, They Say/I Say, which provides specific templates that employ rhetorical effects of written expression, will be integrated weekly into my course design. Specifically, each week I plan to set aside ten to fifteen minutes in class to discuss various topics found throughout these two textbooks. By providing my students with concrete examples of how the writing templates may be used or providing my students examples of how applying rhetorical grammar choices in the early composition phases of writing, will only enhance the readers’ experiences.

One specific example that I can offer from personal experience is what Rhetorical Grammar coins the ‘known-new contract’. A common concern I have witnessed from student feedback and inquiry is whether the essay or connecting paragraphs ‘flow’. The only guidance I ever received on this topic was to make sure the first sentence in a joining paragraph linked to the idea presented in the previous paragraph. Believe me, I agree with students, there is much more that needs to be explained when it comes to creating paragraphs and essays that take the reader through a seamless series of events — enter Rhetorical Grammar and the ‘known-new contract’. The concept teaches the first part of a sentence should be the ‘known’ information found in the preceding sentence. The latter part of the sentence should be the now ‘new’ information, and so it proceeds moving forward. This constant stream of known to new presentation gives the reader a sense of cohesiveness.

Writing for success . . . The lack of cohesiveness and effectiveness of rhetorical appeal found in composition writing can be directly impacted by the inclusion of grammatical “strategy” in the course. Yes, it takes up time in an already limited space. Yes, some students may approach it as ‘boring’. Yes, it is my duty as a professor of English composition to ‘teach’ my students ways that enhance their writing. An analogy I like to give is, “The more tools you have in your toolbox, the better.” My hope is that providing short excerpts of rhetorical grammar theory and implication into my English 1101 classroom will ultimately provide students with a new way of approaching the WRITING PROCESS. Again, my class will be process-oriented and not product-oriented. Yes, the product must manifest; however, I am more concerned with students learning to identify with writing as a process that works across the curriculum and across their professional careers outside of academia. Learning how to make rhetorical choices and not just ‘polish’ and ‘fix commas’ will lead to much greater success in the usage of rhetoric in writing.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020. pixabay.com/illustrations/business-idea-growth-business-idea-3189797/.

Falco. Pixabay, 2020. pixabay.com/photos/hildesheim-germany-lower-saxony-711009/.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say / I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. Fourth edition., W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Hahilove. Pixabay, 2020. pixabay.com/illustrations/light-bulb-ideas-sketch-i-think-487859/.

Kolln, Martha, J., and Loretta S. Gray. Rhetorical Grammar: Grammatical Choices, Rhetorical Effects. Eighth edition, Pearson, 2016.

Micciche, Laura R. “Making a Case for Rhetorical Grammar.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 55, no. 4, 2004, p. 716. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/4140668.

Wokandapix. Pixabay, 2020. pixabay.com/photos/classroom-school-education-learning-2093743/.

-

Journaling in the FYC Classroom

Journaling in FYC Classrooms How can I integrate the process of journaling into an English composition course?

The time has arrived — the moment I begin devising my first-year composition course design to include the syllabus, daily assignments (low stakes writing), and essays (high stakes writing). Over the past seven months, my peers and I have been immersed in pedagogical and practical application theory. From these areas of study, I have identified an area of focus that I would like to implement into my coursework model: journaling. Specifically, my interest in journaling comes from my desire to teach writing as a process, also known as contemplative writing (Miller and Kinane 2), and not just a product. The structural design of contemplative writing provides “. . . a way to explore and encourage the integration of mind, heart, and body in the process of learning” (Miller and Kinane 2).

Holistically, my work at the Kennesaw State University writing center has privileged me to witness how first-year composition students approach their assignments academically as well as emotionally. While students span the spectrums of confidence levels and perceived preparation, I have observed various phases of anxiety, stress, and lack of self-confidence when it comes to completing English 1101 and 1102 essays. Many times, through the course of just discussing the assignment guidelines in great detail, I find students tend to not only relax, but they also tend to get excited about their task at hand; students want to learn but need help navigating, analyzing, and interpreting their assignment guidelines. As a tutor, this signals to me that students want to engage in writing but may be apprehensive about how best to proceed — leading me to become a proponent of process-based pedagogy.

Start with self . . . In the quest to identify ways of helping my future students based upon an in-depth analysis of pedagogical research, I decided to start with myself. To be fair, I must disclose that I love to write; I love everything about it from freewriting, brainstorming, drafting, revision, to the final product. However, I have noticed that while all writers have more learn, a notion I learned from Naming What We Know (Rose 59-61), there is a distinct process that I utilize. This personal process almost always begins with focused freewriting. Interestingly enough, I had no idea there was a term for the process prior to my research. When some of the students that I tutor in the writing center are feeling overwhelmed, or experiencing an unclear sense of direction, I have them pull out a pencil/pen and paper. I then ask students to focus freewrite for a few moments. We take a key term associated with their writing assignment, and I have them write down anything and everything they can think of to get the mind actively engaged with the topic. Most of the time, that’s all it takes! By referring to keywords and phrases, students are then able to begin the brainstorming and/or outlining process. In other words, they go from ideas to creating a map of where their essay or project will continue to develop. Unverzagt (28) further describes this process that I have personally experienced with students: “Disordered and confused as freewriting may be, the aftermath of such explosive expression can be surprising and beneficial. After the students happen upon their thoughts in the ‘discovery draft,’ they can begin to process their sentences and impose a structure upon their writing, reshaping the mass of freewriting into a coherent form.”

Literary Research Research/Literary Analysis

Wanting to incorporate all of these first-hand experiences in conjunction with sound pedagogical theory, I began exploring scholarly research to ascertain the best practices of integrating journaling as a freewriting/focused application into the first-year composition classroom. Explicitly, the question I set out to answer for my course design is:

How can I integrate the process of journaling into an English composition course?

In the words of Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living” (qtd. in Stevens and Cooper 3). Stevens and Cooper discuss commonalities in the lives of those in higher education and argue, “If Socrates’ words echo anywhere, it should be in the academy — where the central goal is the creation of a thoughtful, educated society” (3). This concept leads to the discussion of journaling. First, for clarity, let’s define what a journal encompasses: “. . . sequential, dated chronicle of events and ideas, which includes the personal responses and reflections of the writer (or writers) on those events and ideas” (Stevens and Cooper 5). Boyd and Fales, 1983, defined reflection as “a complex and intentional intellectual activity that generates learning from experience” (qtd. in Stevens and Cooper 19), while Yancey defines reflection as “a process by which we know what we have accomplished and by which, we articulate accomplished products of these processes” (qtd. in Lauer 135). Similarly, Lauer suggests the purpose of writing “. . . as a process of inquiry is to seek insights and new understandings” (135), and D. Godron Rohman suggests, “. . . the journal, as a genre, allows students to access and actualize their true selves” (qtd. in Bawarshi 103). Also entering the academic debate, Reynolds suggests, “freewriting has been considered the ‘healthy habit’ of getting in touch with the unconscious layer of the mind and steering clear of writer’s block” (qtd. in Unverzagt 28). For all of these reasons collectively, there is strong evidential support of introducing first-year composition students to the art and skill of journaling.

Freewriting and Reflection . . . The research has and continues to show that reflection is vital to teaching writing as a process. Journaling is not only a form of free/focused freewriting, but it also can be utilized as a form of reflection in the process of composition writing; “as the term implies, this writing is like a mirror, giving you an opportunity to look at your developing self” (“Journals and Reflective” 72). The inquiry confirmed there is a place for self-reflection and journal writing within composition classrooms. Student testimonials are found throughout the literature of how students “report that they learn to write more fluently and easily” (qtd. in Stevens and Cooper 17). Ultimately, the goal is for students to consider and understand the rhetorical choices they make while engaged in the process of writing. The more students are able to reflect and identify their choices, the easier the writing will become. The easier writing becomes, the more versatile and adaptable it will become, not only across the curriculum but also in life beyond the classroom.

Developmental psychologists Kegan and Drago-Severson have identified two types of learning, informational and transformational (Stevens and Cooper 37), that we will consider regarding how to best implement journaling effectively. Informational learning “involves the acquisition of skills or knowledge, whereas transformational learning involves critical reflection on one’s assumptions . . .” (qtd. in Stevens and Cooper 37). This theoretical approach to learning reminds me of Charles Bazerman’s statement, “Awareness of rhetorical situation is the beginning of reflection on how we perceive the situation, what more we can understand about it, how we can formulate our goals, and what strategies we may take in our utterances” (36). Employing this theory into practice, I plan to implement daily low-stakes journal writing in my English composition classroom.

According to Stevens and Cooper (49), three basic writing principles support journal writing:

- Writing is thinking.

- Practice builds fluency in writing and the motivation to write.

- Students value journal writing when it is fully integrated into the course objectives and structure.

Idea – Brainstorm – Implement Action Plan

While various methods of journaling are used, Luo, Kiewra, Flanigan, and Peteranetz determined that for text-related learning, longhand composition is more beneficial than typing (qtd. in Portman 3). Students will be asked to purchase a composition notebook of their preference that can be used for daily journaling and bring it to each class meeting. The first page of the journal will function as a title page and include the student’s name, course number, and email address. Page two of the journal will be used as a table of contents (TOC) entry only. This will enable students to keep a working TOC throughout the semester in which they can easily access previous entries by topic or activity. Therefore, page numbers will be added to each page of the journal. Grading for completion will occur weekly and count towards the student’s overall course participation grade. According to Stevens and Cooper, students’ journal writing typically accounts for 10-30% of the final grade, with 20% being the most common (48), which I plan on adhering to and disclosing in my syllabus design. The syllabus will explain the motivation and learning outcomes associated with the use of journaling. Currently, the following course objectives in place for first-year composition will be exemplified by the usage of reflective journaling as many of the outcomes involve analysis, interpretation, practice, and composing:

- Practice writing in situations where print and/or electronic texts are used, examining why and how people choose to write using different technologies.

- Interpret the explicit and implicit arguments of multiple styles of writing from diverse perspectives.

- Practice the social aspects of the writing process by critiquing your own work and the work of your colleagues.

- Analyze how style, audience, social context, and purpose shape your writing in electronic and print spaces.

- Craft diverse types of texts to extend your thinking and writerly voice across styles, audiences, and purposes.

Concept Mapping – Brainstorming – Reflection – Summarizing Integrating journal writing into the course design and objectives will provide greater value from students’ perspectives. Based primarily upon ideas found in the research of Stevens and Cooper (77-105), I plan on incorporating the following types of journaling activities as low-stakes writing opportunities weekly:

- Freewriting – just as it sounds, students will be given opportunities to write about whatever is on their mind. Most of the time, this activity will be incorporated in the first few moments of class. I feel as though it will give students time to shift gears and prepare for the classroom activity or discussion that day.

- Focused Freewriting – similar to freewriting, however, a specific keyword, concept, topic, or idea will be provided for the student to then “freewrite” anything and everything that comes to mind for that particular element. This type of exercise may be useful in helping students identify research paper and essay topics of choice.

- Brainstorming – brainstorming will be used to help students formulate and narrow thesis statements for their essays. It may also be used to identify areas for discussion within essays such as bullet point ideas for body paragraphs.

- Concept mapping – the drawing of bubble diagrams may be helpful to students in lieu of traditional outlining. Some students portray a negative stigma towards traditional outlining as sometimes it induces a negative connotation from prior writing experiences. A bubble diagram will offer a similar blueprint but may be viewed as a more graphic and flexible representation of the essay/idea structure.

- Wordcloud generator – word clouds allow students to merge key point ideas and terms. They may be useful to incorporate vocabulary and critical thinking exercises.

- Metareflection – by reading previous journal entries throughout the course of the semester, students will have the opportunity to learn from what they have written. In other words, they will reflect on their freewriting reflection. This process not only teaches students to identify their rhetorical choices, but it also teaches students that revision and reflection are part of the writing process.

- Summary/Analysis – weekly required student readings will take place from the course textbook. However, research shows as few as 30% of students complete readings before the lecture (Stevens and Cooper 102). To help circumvent this scenario, students will summarize and/or reflect on assigned readings in their composition notebooks.

Writing: A Process of Life-Long Learning In summary, I am thrilled to learn that research in the field of rhetoric and composition supports the use of journaling in the English composition classroom. By providing students exposure to various types of journaling (mentioned above), they will begin to learn and develop their own “go-to” methods of prewriting, writing, revision, and reflection — the core components of the writing process. Replacing negative feelings, stigmas, and preconceived ideas with positive, supportive, and procedural attitudes, skills, and processes will foster a successful integration of writing not only in the academic classroom but in society as a whole.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/idea-plan-action-success-concept-1855598/.

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/skills-can-startup-start-up-3371153/.

Bawarshi, Anis S. “Genre and the Invention of the Writer: Reconsidering the Place of Invention in Composition.” Utah State University Digital Commons, 2003, p. 103, digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1140&context=usupress_pubs.

Bazerman, Charles. “Writing Speaks to Situations Through Recognizable Forms.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 35-37.

Clark, Hilary. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/journal-desk-wood-notebook-writing-1090599/.

Gellinger, Gerhard. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/books-read-learn-literature-3322275/.

“Journals and Reflective Writing.” WAC Clearinghouse, pp. 72-93. wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/involved/chapter4.pdf. Accessed 18 Feb. 2020.

Keller, Stefan. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/fantasy-eyes-forest-aesthetic-face-2824304/.

Kunze, Ralf. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/balance-meditation-meditate-silent-110850/.

Lauer, Janice M. “Invention in Rhetoric and Composition.” Parlor Press and WAC Clearinghouse, 2004, p. 135, wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/lauer_invention/lauer.pdf.

Miller, Marlowe, and Karoyn Kinane. “Contemplative Writing Across the Disciplines.” WAC Clearinghouse, pp. 1-5, wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/contemplative/intro.pdf. Accessed 18 Feb. 2020.

Portman, Steve. “Reflective Journaling: A Portal Into the Virtues of Daily Writing.” The Reading Teacher, 2019, pp. 1-6, EBSCOhost, doi:10.1002/trtr.1877.

Rose, Shirley. “All Writers Have More to Learn.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, Classroom Edition, edited by Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2016, pp. 59-61.

Stevens, Dannelle D., and Joanne E. Cooper. Journal Keeping : How to Use Reflective Writing for Effective Learning, Teaching, Professional Insight, and Positive Change. Stylus Publishing, LLC., 2009.

TeroVesalainen. Pixabay. 2020, pixabay.com/photos/mindmap-brainstorm-idea-innovation-2123973/.

Unverzagt, Dori. “Freewriting: A Rationale and Techniques for Use in the First-Year Writing Classroom.” Kentucky English Bulletin, vol. 67, no. 2, Spring 2018, pp. 26–31. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=eue&AN=130403968&site=eds-live&scope=site.

-

FYC Goals: From Theory to Application

From Theory to Application . . . The pendulum is swinging, and with each tick of the clock, I find myself getting closer and closer to that first moment of comprehension — the one where I face twenty-six incoming freshman students that are as apprehensive of taking a writing course as I am teaching it for the first time. Did I design my curriculum to best meet the needs of my students? Are my learning outcomes in line with the course objectives? Are my assignment guidelines structured in a format that facilitates both clarity and cohesiveness? Is the sequencing and scaffolding design of the semester’s assignments logically chronological? As Teresa Redd references, “Talkin bout Fire Don’t Boil the Pot” (146). In other words, studying composition pedagogy may prepare me for understanding the needs of students, and may offer direction on how to best design the course, but all of this does not TEACH the students WRITING; hence, this is where the professor’s role comes into play.

After months of trying to absorb as much as I can researching different theoretical pedagogical perspectives, I now begin the process of mapping out assignments while considering the fundamental takeaways I feel are most critical to incorporate. Several takeaways stand out to me in the readings for this week and are highlighted below:

Audience Matters . . . Diversity in Writing. - Diversity in writing – “To develop students’ rhetorical knowledge and sense of authorship so that they can adapt writing to different purposes, audiences, and contexts” (Redd 147).

Coming from an occupational field outside of academia, I genuinely understand the need for students to be able to transfer writing skills from an academic to an applied setting. Learning how to write for audiences outside of the college classroom is something all students should be exposed to. Upon graduation, students may be tasked with various genres of writing: professional emails, corporate marketing, newspaper articles, social media postings, and for some, creative writing.

Writing for knowledge . . . - We write to learn – “ . . . writing enables us to think in ways that are virtually impossible without writing because we can reflect upon our thoughts more easily when we can see and preserve them” (Redd 148).

I have seen this scenario play out daily while working in the KSU writing center. Sometimes, students will come into the writing center and feel overwhelmed by the task at hand. In this situation, after carefully reviewing the professor’s assignment guidelines, I will begin the freewriting and/or brainstorming process. Often times, students will start to develop a structure or pattern based solely upon what they have written in these brainstorming sessions. I associate this process directly with “we write to learn” — we don’t know what we know until we write it. Furthermore, students recognize the fact they DO know something about what they would like to write.

Identifying your process is key . . . - Writing is a process – “We cannot truly teach writing without teaching the process of writing, for it is the development of flexible processes that will enable students to fulfill the wide range of writing tasks they will encounter in the university and beyond” (Redd 149).

As I have previously discussed in one of my recent blog posts, I believe teaching the processes of writing is very paramount in students’ success of not just freshman-level English composition, but I believe it is fundamental in helping students write BEYOND the current assignment. I met with a student just yesterday that has always enjoyed writing and has had great success in writing. For some reason, the current assignment was overwhelming them to the point they had writer’s block. I immediately began talking to the student to try and identify “processes” they had relied upon and typically used throughout the years that had seemed to work. Within a matter of a few moments, the student was writing again, which wasn’t due to anything I said other than encouraging them to draw upon their “processes.”

Genres of Writing . . . - Understanding different genres of writing – “Conventions make it easier for readers to comprehend a text, in large part because conventions fulfill readers’ expectations” (Redd 150).

Not only do students need exposure to writing across different genres for various types of audiences, but they also need to learn and understand the concept of genres and why they exist. For example, the characteristics of a personal email are quite different compared to the audiences’ expectations of a professional email. For one, professional emails typically require the writer to formally introduce themselves, persuade or inform their audience of a specific event/need, and request a call to action. Usually, none of those characteristics mentioned above would need to be included in a personal email. If students haven’t been introduced to various genres of writing, they won’t understand the needs and expectations of writing within those specific spaces.

Multimodality in Writing . . . - Multimodal writing – “To be truly literate, students need to choose appropriate technology for their role, purpose, and audience . . . At the same time, students need to incorporate technology to save time, paper, and energy” (Redd 151).

Multimodal writing is prevalent in today’s society, and I suspect it isn’t disappearing any time soon. If anything, it is here to stay. Understanding the prescriptive guidelines in multimodal writing and expression will help students identify and align with their intended audiences. For example, having students write a research essay on a topic of choice teaches and reinforces field research. Once the essay is completed, professors could have students compose a multimodal assignment (blog post, travel brochure, etc.) incorporating the same research as incorporated into the essay. This type of assignment would aid students in understanding how the same information can be presented in a multimodal and multidimensional environment.

Works Cited

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/tutor-coach-teacher-manager-407361/.

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/puzzle-planning-strategy-process-1686920/.

Altmann, Gerd. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/social-social-media-communication-3064515/.

Free-Photos. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/photos/audience-crowd-people-persons-828584/.

Iqbal, Mudassar. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/illustrations/webdesign-design-web-website-3411373/.

OpenClipart-Vectors. Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/vectors/hand-pencil-pen-edit-eraser-write-160538/.

Reed, Teresa. “Talkin bout Fire Don’t Boil the Pot: Putting Theory into Practice in a First-Year Writing Course at an HBCU.” First-Year Composition: From Theory to Practice, edited by Coxwell-Teague, Deborah and Ronald F. Lunsford, Parlor Press, 2014, pp. 146-166.

-

The Pedagogy of Scaffolding

How do the pieces connect? One of the biggest challenges I believe teachers face is bridging the gap between theoretical pedagogy and application. Haven’t we all heard sayings such as: “why do I need this?”, “I won’t use this ever again,” “this has nothing to do with my major,” “this is something that doesn’t happen in the ‘real world.’” As a student myself, I am not far removed from these mumblings that students whisper in the hallways. However, switching hats, so to speak, lends a newfound appreciation for the task that college professors face daily — how to convert theory into practice in an applied setting that “bridges the gap” for students. Put simply, the process of not just analyzing pedagogical theory, but the practice of dissecting its roots and integrating those roots into instruction. Let’s discuss this process!

The Sweetland Center for Writing at the University of Michigan put forth an article titled Effective Assignment Sequencing for Scaffolding Learning. To date, this has been the most beneficial article that I have read on providing concrete examples of assignments and processes that teachers and professors can implement. Studying the reasoning behind scaffolding assignments is a long way from learning how to take the conceptual theory of WHY we (professors) scaffold assignments and HOW to scaffold assignments. Interestingly enough, I am thrilled to report that as I read through the suggestions of low stakes to high stakes assignments, I found myself smiling; it was almost as though I could anticipate what was to come next. Why? Well, because I have discovered that the “theory” I am studying is something I am already MOST familiar with because my professors have and continue to use the same structure on me!!!

All writers have more to learn! So, giving you a chance a catch-up, or, rather, giving myself a chance to breathe, let’s look at that last statement, again. Yes, the same suggested methods of scaffolding used in Sweetland’s article are the same methods that my instructors have used to help us (my cohort) understand, learn, absorb, and comprehend the material being presented in class. As Sweetland suggests, “each assignment practices old skills and provides new skills students will also need to finish the next assignment” (par. 3). Several key items struck me and are concepts that I plan to incorporate in the near future while designing an English 1101 coursework portfolio. These items are listed below, and comparisons are made as to how I plan to utilize them next semester.

- Simple to complex: Yes, it seems simple, but isn’t always practiced in classroom pedagogy. We have all had that “course” where we jump into a large project and frantically begin googling anything we can find on “how to.” I strongly feel this shouldn’t be the case. As professors, we should be “scaffolding” our assignments to begin with simple aspects of the overall project and working our way up to more complex elements affiliated with the project/assignment. For example, having students “. . . practice summarizing course readings before they attempt to analyze them” is a simple to complex practice mentioned in the Sweetland article (par. 2).

- Revision is key: Yes, this is a thresholds concept we studied last semester. According to Sweetland, “Built-in, low stakes revision activities also have the benefit of undermining common bad habits by positioning writing as more than the typical two-stage drafting process . . .” This is something I can most definitely attest to after working in the KSU writing center. Often times, students come into the center on their first or second draft wanting to “proofread” their papers. The process of revision seems to escape many students. I believe giving students some type of course credit for the “revising” portion of their assignment will enable them to begin bridging a gap between “I’m done” to “let’s review this again.” As I have seen in the writing center, initially, students are keener on considering revision when there are points assigned to the process.

- Practice engaging the material: Yes, I, too, have complained about discussion board postings in some of my graduate courses. Sometimes they feel like “busy work” at first glance. However, I have found that what I thought was “read this and leave some specific thoughts about it” turned into genuinely beginning to understand and work with the ideas found within those articles to build upon the next assignment. For example, an assignment in one of my courses was to read a few chapters on English dialects in various United States’ regions. Although it was interesting, the material was very dense, and I found myself losing intimate details as I left one region and began another; in other words, my retention of the content was challenging at best. But the next assignment expanded the same concept into international regions and the differences within English dialects in those areas. Without a doubt, the research I completed for different dialects of English within the U.S. helped me to understand the material I was researching for international dialects.

- Pre-Writing Assignments: Yes, many students shudder at the concept of pre-writing. “I don’t outline” is something I have heard many times while working in the writing center. For some reason, there appears to be a negative connotation with the term “outline.” I’m not sure if this is due to mandatory practices in previous courses, but I believe you could describe the same process as outlining but term it something else, such as “mapping,” and students would offer a more positive response. Sweetland suggests a project proposal design that “ . . . provide an opportunity for students to articulate what they want to accomplish with a project as well as generate feedback from you and/or from their peers” (par. 8). Structurally, the project proposal directive enables students to “brainstorm” without realizing they are “brainstorming.” It also gives students the ability to create a mental “outline” without having to produce a traditional “outline.” I would suggest it is virtually impossible to write/draft a project proposal without (at least mentally) working out the “blueprint” of what, where, how, why, and when the project will need/address.

Below is a video by Texas A & M University Writing Center that gives some very helpful tips students can use for the pre-writing process:

Pre-writing for success! While I could probably go one for pages yet to come, I want to wrap this blog post up by saying the most influential takeaway from the Sweetland article, for me, is the concept of reflective writing. For years I have written whatever came to mind at the time when needed to draft an assignment or essay. It wasn’t until this past semester in graduate school that reflective writing was introduced to me. At first, I found it quite challenging to express the reasons behind the rhetorical choices I made in essay composition. Once I fumbled through the first few paragraphs, I realized that by reflecting on my writing style and the choices I made in writing enabled me to write more expressively in future draftings. Stated another way, as a writer, once I began to identify “why” I wrote “what” I wrote, I was then able to make more deliberate statements that tend to be more powerful and provide better clarity. As always, ALL writers have more to learn, and by utilizing the method of self-reflection, I hope my writing continues to improve and delivery enhanced. Sweetland breaks the reflection component down to the following three sectors (par. 12):

- Changes they’ve made to their final draft

- Why and how they made those changes

- What those changes demonstrate about their thinking/writing development

Rome wasn’t built in a day . . . Final takeaway — the cliché Rome wasn’t built in a day applies to many facets in life, writing included! Before learning sentence structures, students must learn vocabulary. Before learning essay construction, students must learn paragraph construction. Integrating low stakes to high stakes writing in the composition classroom, known as scaffolding assignments, will provide students with a better understanding of not only WHY they are completing an assignment or project, but will also help bridge the gap between theory and practice. When a student understands why they are completing a task and reflects on the choices they made, the likelihood they are able to transfer those same skills to other facets in life is more likely.

Works Cited

B., Thomas, Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/photos/strommast-power-generation-4459235/.

“Brainstorming.” YouTube, uploaded 8 March 2016 by Tamuwritingcenter, youtube.com/watch?v=HSufG-AIQYo.

“Effective Assignment Sequencing for Scaffolding Learning.” Sweetland Center for Writing, University of Michigan, lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/instructors/teaching-resources/sequencing-and-scaffolding-assignments.html. Accessed 4 February 2020.

OpenClipart-Vectors, Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/vectors/colosseum-italy-romans-rome-ruin-1296587/.

Vasek, Jan, Pixabay, 2020, pixabay.com/photos/laptop-woman-education-study-young-3087585/.